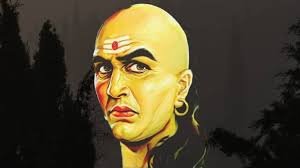

Chanakya (IAST: Cāṇakya, pronunciation (help·info)) was an ancient Indian teacher, philosopher, economist, jurist and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya or Vishnugupta, who authored the ancient Indian political treatise, the Arthashastra,[3] a text dated to roughly between the 4th century BCE and the 3rd century CE.[4] As such, he is considered the pioneer of the field of political science and economics in India, and his work is thought of as an important precursor to classical economics.[5][6][7][8] His works were lost near the end of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century CE and not rediscovered until the early 20th century.[6]

Chanakya assisted the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta in his rise to power. He is widely credited for having played an important role in the establishment of the Maurya Empire. Chanakya served as the chief advisor to both emperors Chandragupta and his son Bindusara.

Buddhist version

The legend of Chanakya and Chandragupta is detailed in the Pali-language Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. It is not mentioned in Dipavamsa, the oldest of these chronicles.[10] The earliest Buddhist source to mention the legend is Mahavamsa, which is generally dated between 5th and 6th centuries CE. Vamsatthappakasini (also known as Mahvamsa Tika), a commentary on Mahavamsa, provides some more details about the legend. Its author is unknown, and it is dated variously from 6th century CE to 13th century CE.[11] Some other texts provide additional details about the legend; for example, the Maha-Bodhi-Vamsa and the Atthakatha give the names of the nine Nanda kings said to have preceded Chandragupta.

Jain version

The Chandragupta-Chanakya legend is mentioned in several commentaries of the Shvetambara canon. The most well-known version of the Jain legend is contained in the Sthaviravali-Charita or Parishishta-Parvan, written by the 12th-century writer Hemachandra.[1] Hemachandra’s account is based on the Prakrit kathanaka literature (legends and anecdotes) composed between the late 1st century CE and mid-8th century CE. These legends are contained in the commentaries (churnis and tikas) on canonical texts such as Uttaradhyayana and Avashyaka Niryukti.[13]Thomas Trautmann believes that the Jain version is older and more consistent than the Buddhist version of the legend.[13]

Kashmiri version

Brihatkatha-Manjari by Kshemendra and Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva are two 11th-century Kashmiri Sanskrit collections of legends. Both are based on a now-lost Prakrit-language Brihatkatha-Sarit-Sagara. It was based on the now-lost Paishachi-language Brihatkatha by Gunadhya. The Chanakya-Chandragupta legend in these collections features another character, named Shakatala (IAST: Śakaṭāla).[14]

Mudrarakshasa version

Mudrarakshasa (“The signet ring of Rakshasa”) is a Sanskrit play by Vishakhadatta. Its date is uncertain, but it mentions the Huna, who invaded northern India during the Gupta period. Therefore, it could not have been composed before the Gupta era.[15] It is dated variously from the late 4th century[16] to the 8th century.[17] The Mudrarakshasa legend contains narratives not found in other versions of the Chanakya-Chandragupta legend. Because of this difference, Trautmann suggests that most of it is fictional or legendary, without any historical basis.

Buddhist version

According to the Buddhist legend, the Nanda kings who preceded Chandragupta were robbers-turned-rulers.[10] Chanakya (IAST: Cāṇakka in Mahavamsa) was a Brahmin from Takkāsila (Takshashila). He was well-versed in three Vedas and politics. He had canine teeth, which were believed to be a mark of royalty. His mother feared that he would neglect her after becoming a king.[2] To pacify her, Chanakya broke his teeth.[23]

Chanakya was said to be ugly, accentuated by his broken teeth and crooked feet. One day, the king Dhana Nanda organized an alms-giving ceremony for Brahmins. Chanakya went to Pupphapura (Pushpapura) to attend this ceremony. Disgusted by his appearance, the king ordered him to be thrown out of the assembly. Chanakya broke his sacred thread in anger, and cursed the king. The king ordered his arrest, but Chanakya escaped in the disguise of an Ājīvika. He befriended Dhananada’s son Pabbata, and instigated him to seize the throne. With help of a signet ring given by the prince, Chanakya fled the palace through a secret door.[23]

Chanakya escaped to the Vinjha forest. There, he made 800 million gold coins (kahapanas), using a secret technique that allowed him to turn 1 coin into 8 coins. After hiding this money, he started searching for a person worthy of replacing Dhana Nanda.[23] One day, he saw a group of children playing: the young Chandragupta (called Chandagutta in Mahavamsa) played the role of a king, while other boys pretended to be vassals, ministers, or robbers. The “robbers” were brought before Chandragupta, who ordered their limbs to be cut off, but then miraculously re-attached them. Chandragupta had been born in a royal family, but was brought up by a hunter after his father was killed by an usurper, and the devatas caused his mother to abandon him. Astonished by the boy’s miraculous powers, Chanakya paid 1000 gold coins to his foster-father, and took Chandragupta away, promising to teach him a trade.[24]

Chanakya had two potential successors to Dhana Nanda: Pabbata and Chandragupta. He gave each of them an amulet to be worn around the neck with a woolen thread. One day, he decided to test them. While Chandragupta was asleep, he asked Pabbata to remove Chandragupta’s woolen thread without breaking it and without waking up Chandragupta. Pabbata failed to accomplish this task. Some time later, when Pabbata was sleeping, Chanakya challenged Chandragupta to complete the same task. Chandragupta retrieved the woolen thread by cutting off Pabbata’s head. For the next seven years, Chanakya trained Chandragupta for royal duties. When Chandragupta became an adult, Chanakya dug up his hidden treasure of gold coins, and assembled an army.[24]

The army of Chanadragupta and Chanakya invaded Dhana Nanda’s kingdom, but disbanded after facing a severe defeat. While wandering in disguise, the two men once listened to the conversation between a woman and her son. The child had eaten the middle of a cake, and thrown away the edges. The woman scolded him, saying that he was eating food like Chandragupta, who attacked the central part of the kingdom instead of conquering the border villages first. Chanakya and Chandragupta realized their mistake. They assembled a new army, and started conquering the border villages. Gradually, they advanced to the kingdom’s capital Pataliputra (Pāṭaliputta in Mahavamsa), where they killed the king Dhana Nanda. Chanakya ordered a fisherman to find the place where Dhana Nanda had hidden his treasure. As soon as the fishermen informed Chanakya about its location, Chanakya had him killed. Chanakya anointed Chandragupta as the new king, and tasked a man named Paṇiyatappa with eliminating rebels and robbers from the kingdom.[25]

Chanakya started mixing small doses of poison in the new king’s food to make him immune to poisoning attempts by the enemies. Chandragupta, who was not aware of this, once shared the food with his pregnant queen, who was seven days away from delivery. Chanakya arrived just as the queen ate the poisoned morsel. Realizing that she was going to die, Chanakya decided to save the unborn child. He cut off the queen’s head and cut open her belly with a sword to take out the foetus. Over the next seven days, he placed the foetus in the belly of a goat freshly killed each day. After seven days, Chandragupta’s son was “born”. He was named Bindusara, because his body was spotted with drops (bindu) of goat’s blood.[25]

The earliest Buddhist legends do not mention Chanakya in their description of the Mauryan dynasty after this point.[24] Dhammapala‘s commentary on Theragatha, however, mentions a legend about Chanakya and a Brahmin named Subandhu. According to this account, Chanakya was afraid that the wise Subandhu would surpass him at Chandragupta’s court. So, he got Chandragupta to imprison Subandhu, whose son Tekicchakani escaped and became a Buddhist monk.[26] The 16th-century Tibetan Buddhist author Taranatha mentions Chanakya as one of Bindusara’s “great lords”. According to him, Chanakya destroyed the nobles and kings of 16 towns and made Bindusara the master of all the territory between the eastern and the western seas (Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal).[27]